Sustainability in Fibres

Sustainability in Fibres

Created by Redress

The role of fibres in circularity

There is not one ‘perfect’ fibre. Across every product’s lifecycle, from raw material to end-of-life, there is an environmental impact, but you have the ability to significantly reduce it. Of the total fibre input used for clothing, 87% is landfilled or incinerated, representing lost opportunities of more than US$100 billion annually. [1] Your choices to use regenerative resources, innovative spinning methods, and non-hazardous finishing treatments can make the difference to reduce negative environmental impact at source.

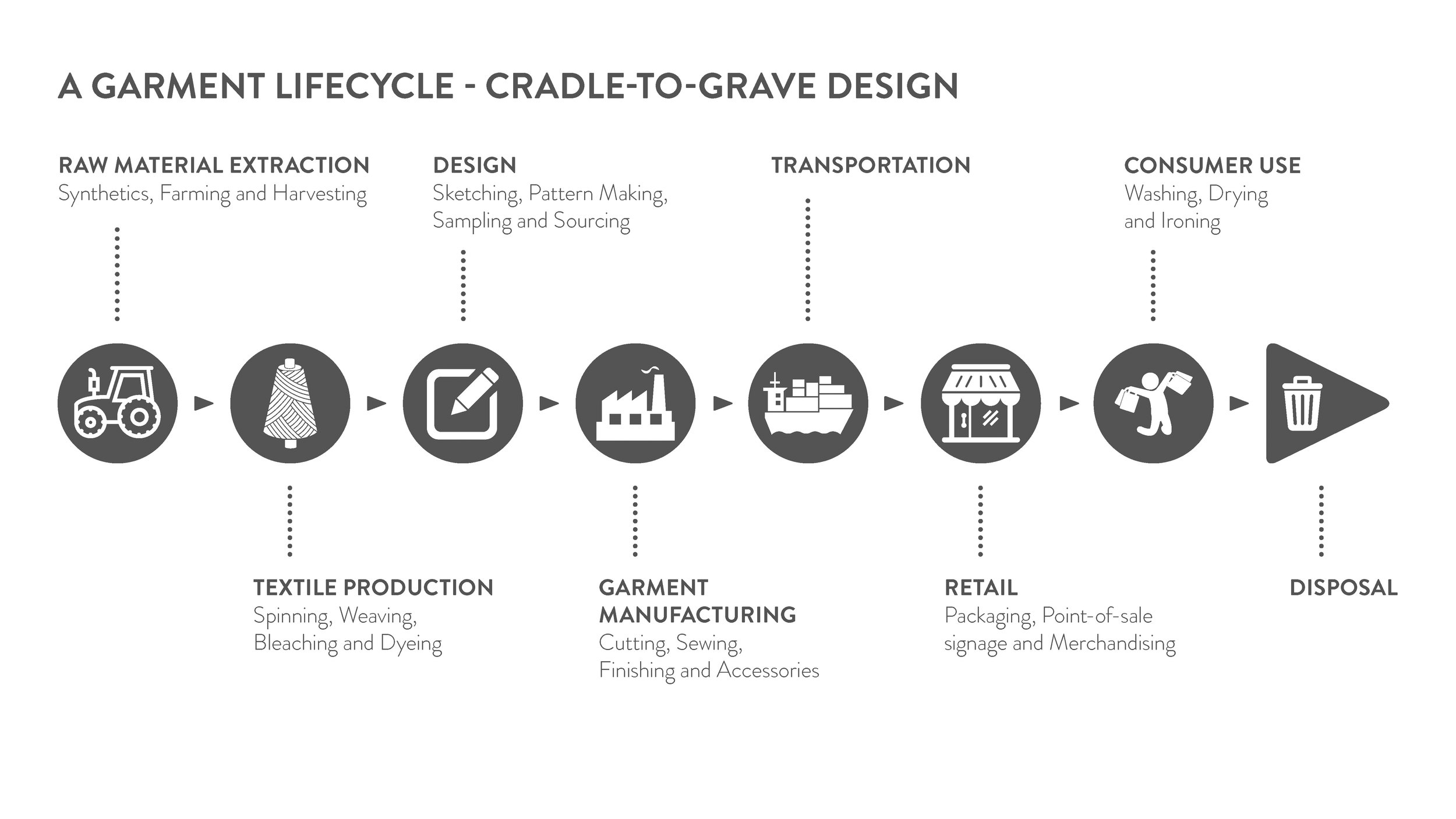

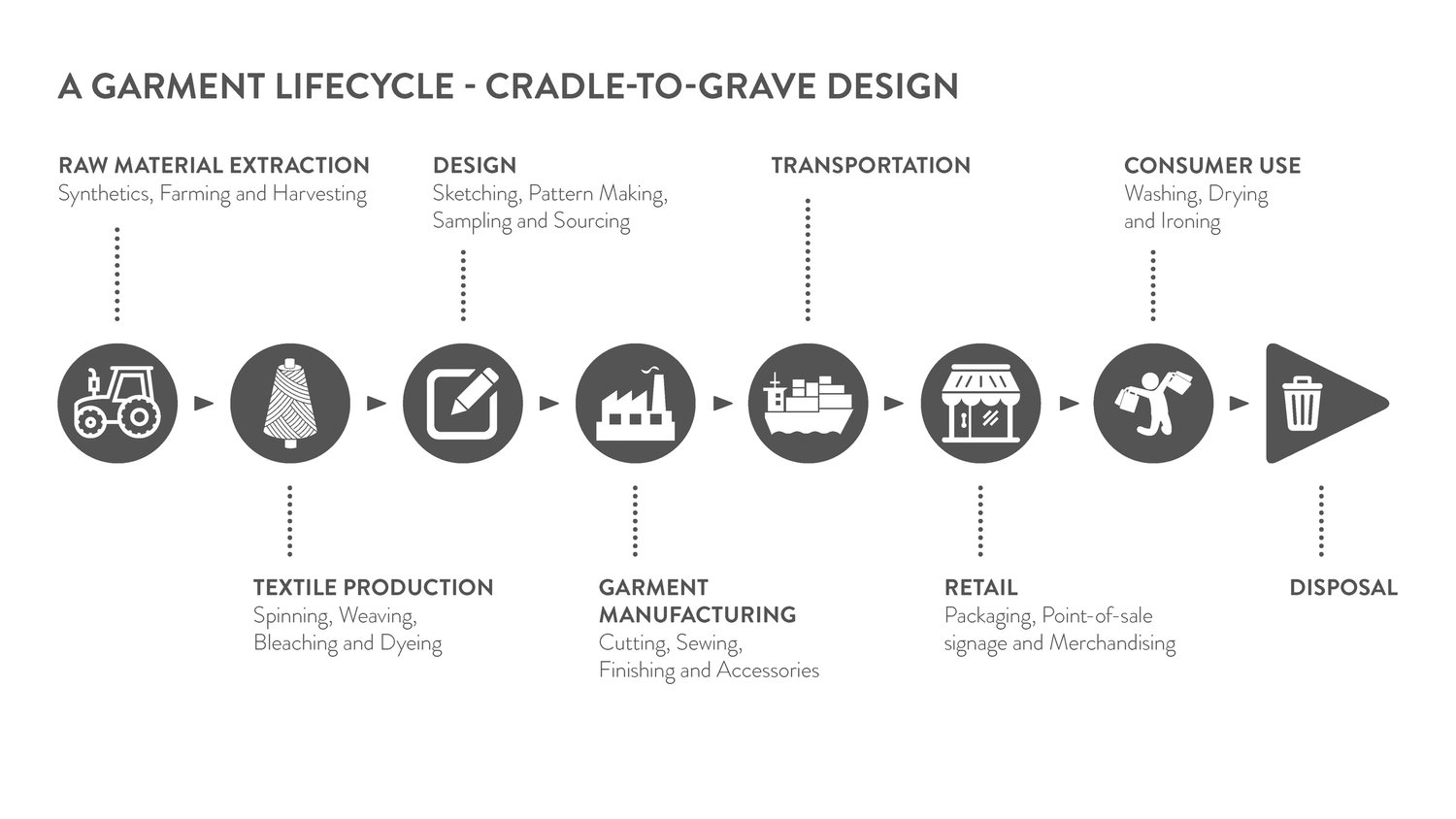

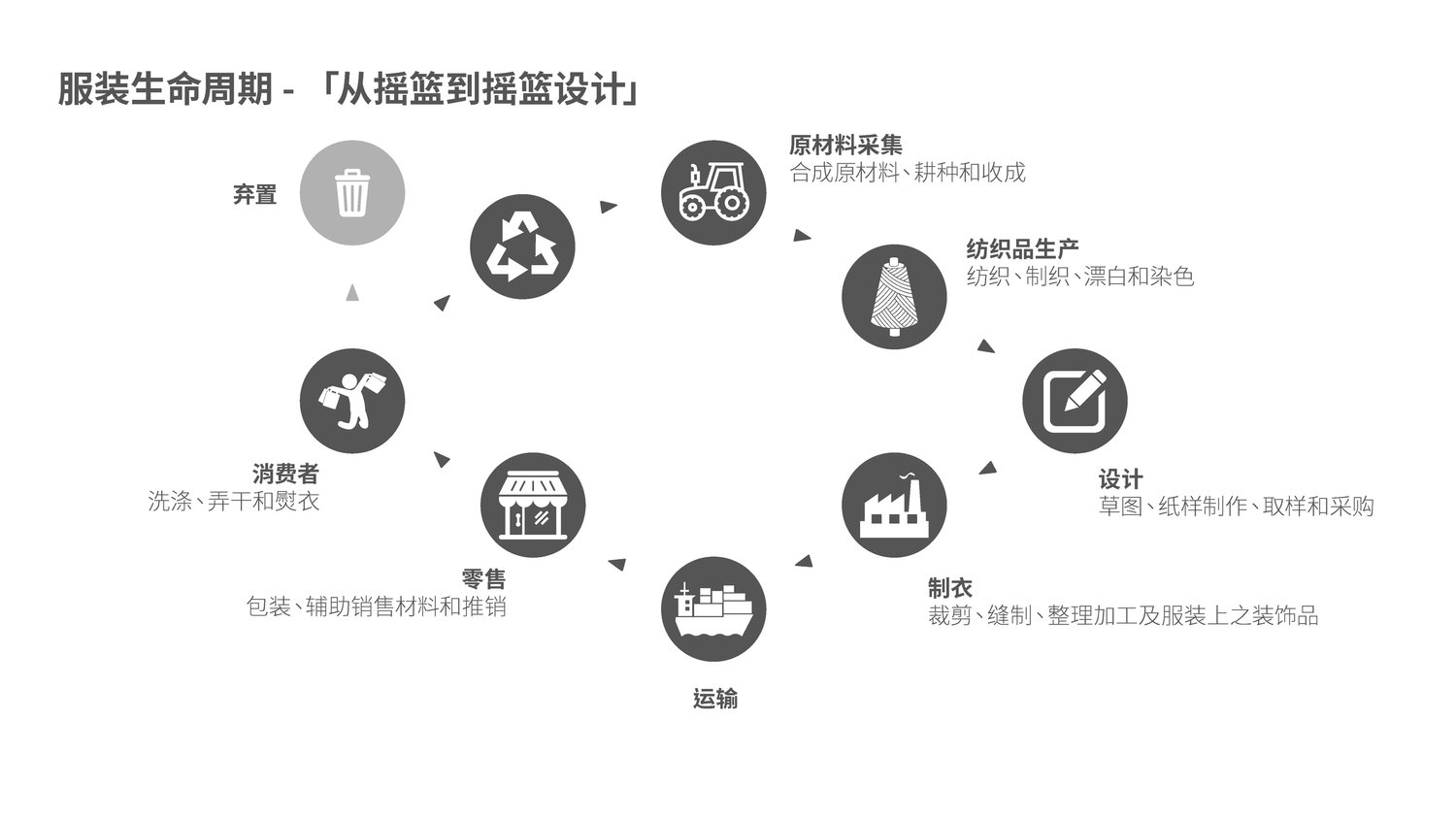

A garment lifecycle: cradle-to-grave design

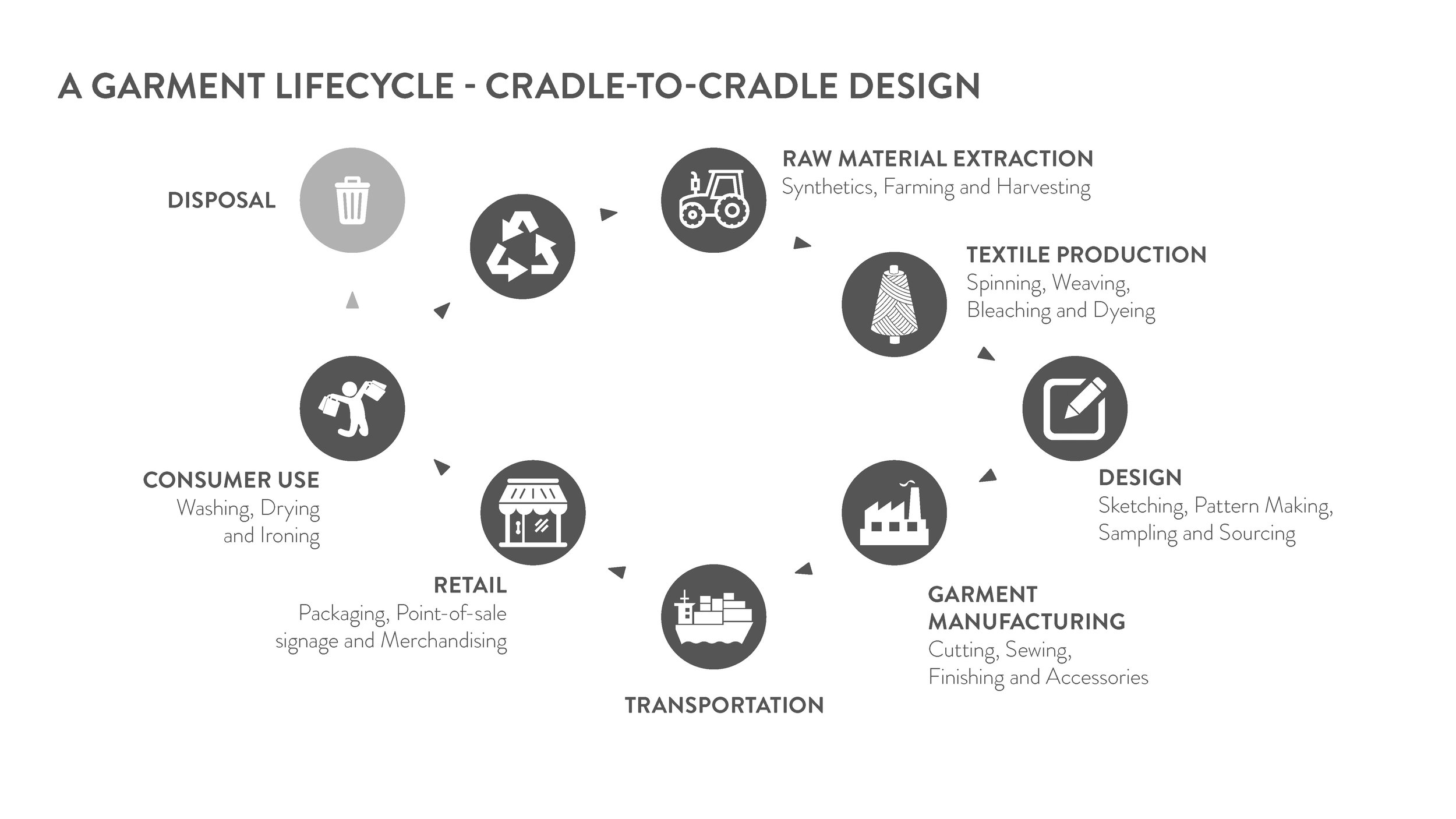

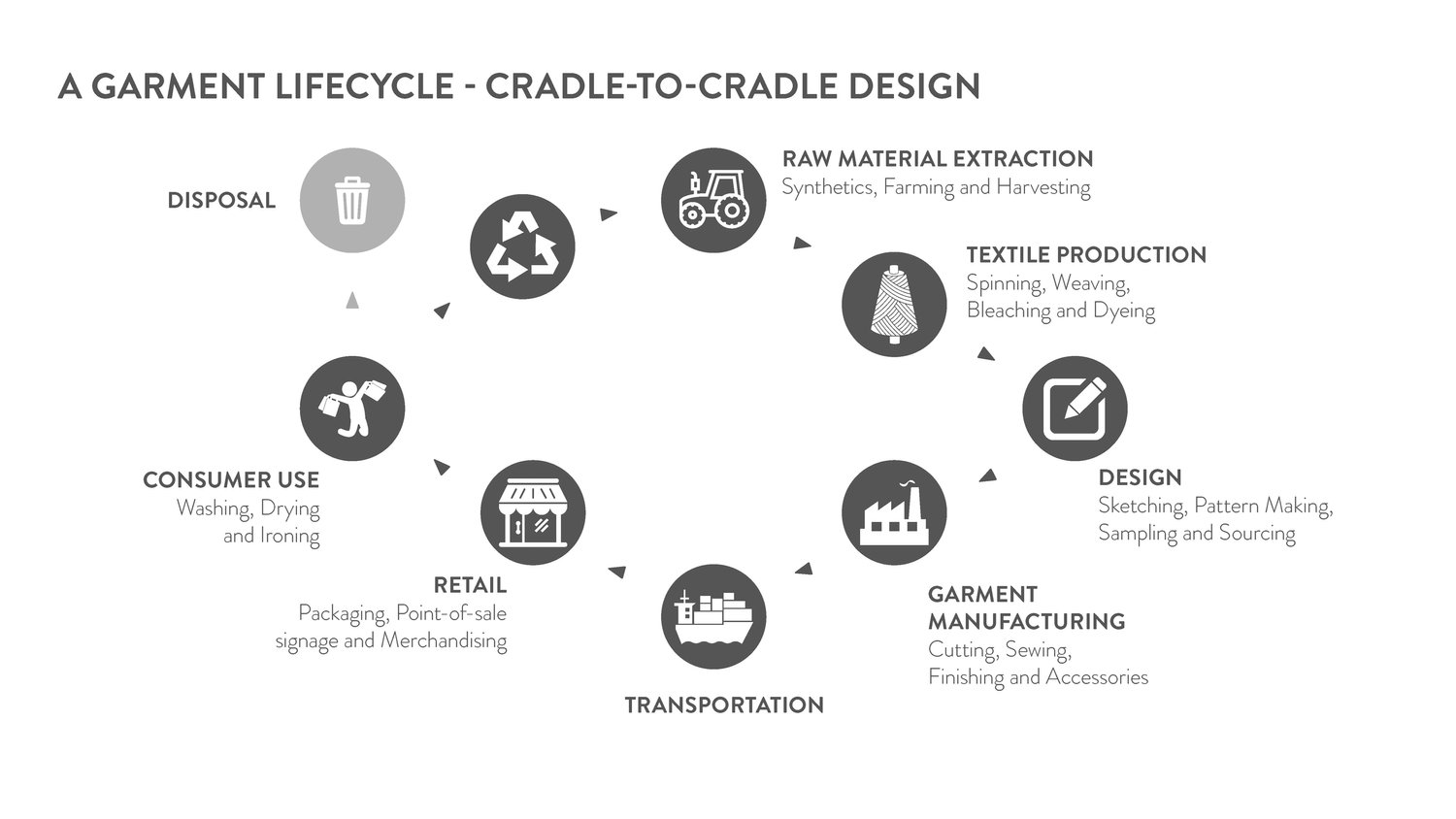

A garment lifecycle: cradle-to-cradle design

As a professional working in the fashion industry, you will need to understand the transformation from the linear to circular model, where fibres play a key role in diverting textiles from disposal back into the system through recycling, upcycling, and other innovative methods. This is key, because the industry is facing growing environmental challenges and the landscape of fashion professions is continually evolving. Whether you have plans to start your own fashion brand or work within an established one, building your knowledge on circularity will give you an edge in your career.

Expert Tip

Bojana Drača

Designer of Farrah Floyd

I think the most important thing to know, for a designer who is trying to run a sustainable fashion brand, is that almost nothing is entirely sustainable. By summarising all the available information and making a choice that reduces impact on people and the environment, then we know we are doing something good. Every case is different, and every fibre is different. It can be more or less sustainable depending on the perspective we are looking from.

Image credit: Farrah Floyd

Bojana Drača’s sustainable brand, Farrah Floyd, focuses on zero-waste designs made using sustainable textiles.

Fibres categorisation

Understanding what a material is made from is the beginning of creating fundamental change towards circular fashion systems. Traditionally, raw materials are extracted from natural resources such as oil, plants, trees, and animals, and are then processed into fibres, which are categorised as either natural or man-made:

- NATURAL FIBRES

- PLANT-BASED (commonly described as cellulose-based)

Examples of fibres that are harvested from plants are cotton, linen, hemp, and jute. - ANIMAL-BASED (commonly described as protein-based)

Examples of fibres that come from animal coats include wool, silk, and down.

- PLANT-BASED (commonly described as cellulose-based)

- MAN-MADE FIBRES

- CELLULOSE (MMCF)

Man-made cellulosic fibre (MMCF) is created from natural feedstock such as trees and plants using a chemical process to soften them for extraction to become fibres. Examples include viscose/rayon, modal, bamboo, lyocell, cupro, and acetate (modified). - SYNTHETIC

Created by chemical synthesis, synthetic fibre comes from oil-based polymers. Examples include polyester, nylon, acrylic, polypropylene, and spandex.

- CELLULOSE (MMCF)

Manufacturing fibres is a complex process which can produce endless compositions and characteristics. In order to understand the environmental impact, we will introduce the most commonly used fibres: cotton and polyester.

COTTON

Cotton is grown from a plant and represents the bulk of the natural fibre market share. It is the second most utilised fibre in terms of volume. With about 24.7 million tonnes, it had a market share of approximately 22% of global fibre production in 2021. [2] Although we hear a lot about organic cotton in the market, only 1% of global cotton production can qualify as organic, while the other 99% is considered conventional [3]. No matter how cotton is grown, most production depends on vast amounts of land, water, fertiliser, and a significant amount of pesticides to control insects, pests, weeds, and chemical additives that regulate growth [4].

As with many fibres that are manufactured at scale, with cotton there are myriad factors across the various stages of production that can have either positive or negative environmental impact on the sustainability of the finished fibre. Below you can explore some examples for conventional cotton.

| Fibre production stage | Positive environmental aspects | Negative environmental aspects |

| Raw materials |

WATER | Cotton relies on vast amounts of water. The average water footprint for just 1kg of cotton (equivalent to a single T-shirt and pair of jeans) is 10,000–20,000 litres.[5] CHEMICALS | Each year, cotton production requires an estimated 200,000 tonnes of pesticides and 8 million tonnes of fertilisers.[6] |

|

| Yarn production | LONG STAPLE | Cotton grows with a long fibre length, called long staple. When used in fabric, the strong cotton fibres can contribute to the longevity of the garment.[7] | ENERGY | Due to the highly mechanised system, spinning fibres into yarn takes up 44% of the total energy consumption of cotton production.[8] |

| Fabric manufacturing | NO NEED FOR CHLORINE BLEACH | Because of its light colour, cotton can be bleached (before dyeing) with relatively safe hydrogen peroxide.[9] | WATER POLLUTION | Fabric is treated with chemicals. Not all of these are hazardous, but some can contain heavy metals which, if left untreated, can cause significant water pollution.[10] |

| Consumer use | RESISTANCE TO INSECTS | Common closet pests, moths and beetles, do not affect or damage cotton garments.[11] | GREENHOUSE GAS EMISSIONS | Traditionally, cotton is washed and dried at high temperatures, which creates higher emissions of greenhouse gases. |

| End of life | RECYCLABLE (mechanically and chemically) and BIODEGRADABLE | All assets of a cotton plant are used and can support a closed loop system.[12] |

POLYESTER

With a market share of 54% of the global total fibre production in 2021, polyester continues to be the most widely produced fibre. The production volume of polyester fibres increased from 57 million tonnes in 2020 to 61 million tonnes in 2021. [13] In order to encourage sustainable fibre production, the apparel industry is being challenged to use recycled polyester, which generally has a significantly lower carbon footprint than conventional polyester. [14] Like conventional cotton, there are both positive and negative environmental impacts to consider when selecting conventional polyester for use in your designs.

| Fibre production stage | Positive environmental aspects | Negative environmental aspects |

| Raw materials | NON-RENEWABLE RESOURCE | Virgin polyester is derived from petroleum, which takes millions of years to form.[15] | |

| Yarn production | HEAVY METALS | Production of fibre and yarns uses heavy metals, specifically antimony, which is a known carcinogen.[16] | |

| Fabric manufacturing | ENERGY SAVING DYE METHODS | Many methods reduce the amount of water and energy used, including electrochemical dyeing, which reuses dyebath, as well as non-aqueous systems, which use carbon dioxide or ionic liquids instead of water. [17] | ENERGY THIRSTY | It takes twice the amount of energy to produce 1kg of polyester compared with 1kg of cotton. [18] |

| Consumer use | REDUCED ENERGY USE | The low absorbency of polyester fibre means that it dries quickly, saving the need to use a dryer. | MICROFIBRES | When washing polyester (or any synthetic fabric), microfibres can shed, enter the water ecosystems, and eventually, our food chain. |

| End of life | RECYCLABLE | Chemical processing allows virgin quality to be reproduced in a closed loop system. [19] | SLOW TO DECOMPOSE | Polyester, a petroleum-based fibre, can take up to 200 years to decay, which is significantly longer than natural fibres. [20] |

BLENDED YARNS

An important consideration for design professionals when selecting fabrics is whether or not it incorporates blended yarns. Blending fibres is common practice as it enables manufacturers to add durability, functionality, and a variety of fibre finishes to garments. [21] The negative aspect of selecting fibre blends is that they require the chemical separation of fibres before they can be recycled, a process which is still very much in development and not yet commercially viable. Mechanical recycling is the most prolific form of textile recycling, but it weakens fibres. In order to be reused for a quality product, these recycled fibres need to be blended with virgin fibres.[22] Due to limitations in recycling, circularity in fibres is currently limited. More often than not, blended fibres end up in industrial products like furniture fillings, carpet pads ,and insulation, or are sent to landfill to join the 92 million tonnes of textile waste created annually by the industry. [23]

Here are some examples of exciting projects innovating on the recyclability of blended fibres:

Images credit: HKRITA & H&M Foundation

The Green Machine is a pre-industrial scale hydrothermal system developed through a collaboration by HKRITA and H&M Foundation. The system has been set up to recycle cotton-polyester blends using only heat, water, and less than 5% of a biodegradable green chemical. The outcome of the recycling process is a recovery rate of over 98% for polyester fibres in 0.5–2 hours, and the creation of cellulose-based powder.

Image Credit: Infinited Fiber

Finnish company Infinited Fiber created Infinna™, a fibre made from cellulose-rich waste including discarded textiles, used cardboard, and even rice straw. Infinna™ has the natural look and feel of cotton, plus unique properties that make it ideal for use in a range of fabrics, from soft single jersey and French terry to denim, shirting fabric, and beyond.

Image Credit: Truetzschler

Yarn companies are now exploring ways of producing high quality yarn from recycled fibres. New innovations in textile machinery, such as Truetzschler, are making this possible for cotton spinners. The TC 19i intelligence card maximises quality and productivity so that high quality yarn can be produced from recycled fibre and material. To learn more about recycling blended fibres, please visit the Redress Academy Design for Recyclability Guide.

How do I make better decisions during fibre selection?

With a growing consensus on the economic and environmental benefits of moving to a circular fashion system, the industry is making significant progress and innovation that can help you make an informed choice on selecting more sustainable fibres. As a designer, this decision on how to reduce your impact can feel overwhelming, but you have tremendous power! Read on for ideas to guide you in selecting alternative fibres and to learn about innovative solutions for circularity.

1 Raw materials

The value of ‘waste’ is increasingly recognised as a resource by the textile and other industries. Trade shows are a great starting place to explore the best fibre options for your designs. Try The Sustainable Angle, which showcases innovative alternatives to conventional fibres, of which there are a growing number on the market.

Image credit: ANANAS ANAM

Piñatex® is created by ANANAS ANAM from feedstock from the food industry. It is a versatile, natural textile, made from the leaves (skins) of pineapple waste.

Image credit: Bolt Threads

Bolt Threads, a US-based company, uses bioengineering to create Microsilk™, a protein fibre that is produced through the fermentation of genetically modified yeast, water, and sugar. The fibre has the same molecular structure as spider silk with a tensile strength comparable to that of steel. The company partnered with Stella McCartney, who used it as an ethical alternative to silk.

Image credit: Mara Hoffman

Lyocell fibre is made from wood or plant pulp, and is both recyclable and biodegradable. Austrian fibre company Lenzing produces TencelTM lyocell, a fibre made from wood certified by the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) and Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification (PEFC). The production of TencelTM lyocell uses solvents in a closed loop process, during which more than 99% of material is recovered and reused. US-based fashion brand Mara Hoffman has made a commitment to only source fibres which are natural, recycled, and renewable, and uses TencelTM lyocell in their collections.

2 Yarn production

The global apparel and footwear industry produced more greenhouse gases than France, Germany, and the UK combined in 2018, totalling 2.1 billion tonnes of CO2 emissions — approximately 4% of total global emissions. Without significant action, the figure could rise to around 2.7 billion tonnes a year by 2030. [24] There are a growing number of alternative yarn options that have been created with consideration for the environment at the forefront. [25]

Image credit: Wolford

ROICA™ V550 by Asahi Kasei is a sustainable alternative to conventional elastane yarn made with less water, scouring agent, energy, and oil content. Austrian lingerie brand Wolford is developing a line of lingerie using ROICA™ V550 elastic, which also decomposes without releasing harmful substances at the end of use.

Image credit: Arket

Organic wool is an alternative to the standard practice of wool farming which uses chemicals on sheep and wool during farming and/or fibre processing. To achieve certification as organic wool, the product must meet the criteria of individual certifying bodies, such as the Global Organic Textile Standard (GOTS). Arket, an H&M owned brand, uses organic wool in their knitwear collections.

3 Fabric and garment manufacturing

On average, 25% of material is cut off during garment production, and in some cases this figure can be 40% or more. [26] Currently, less than 1% of the material used to produce clothing is recycled into new clothing, and just 13% of the industry’s total material input is in some way recycled after it is used for clothes. [27]

In addition, the chemicals used in dyeing, printing, and finishing fabric and garments can also have significant negative environmental impacts. Approximately 280,000 tons of largely nonbiodegradable dyes are discharged annually, either to wastewater treatment plants or directly to the environment. [28]

A growing number of brands and manufacturers are taking the initiative to change methods of processing fabric and garments in order to decrease pollution. To support these efforts, governments are tightening regulations in manufacturing regions to curb the current pollution levels. China announced targets to spin 25% of its domestic textile waste into new fibres by 2025. [29] The challenge is to clean up existing pollution while maintaining manufacturing outputs and developing less polluting processes.

Here are some examples of innovative processes that can be used in fabric and garment manufacturing:

Image credit: Levi’s

Levi Strauss & Co’s collaboration with laser technology from Jeanologia led to Project F.L.X. (future-led execution), which uses lasers and automation to reduce chemicals and hand sanding from the finishing process.

Image credit: Kowtow

A good way to ensure your fabric meets environmental regulations is to use certified fabrics, where independent third party testing is required. One example of this is the Global Organic Textile Standard (GOTS), which considers water and chemical usage throughout production stages. Sustainable womenswear brand Kowtow is built on certifications and uses GOTS-approved dyes and inks in fabrics and prints.

Image credit: High Fashion (China) Co.

The Global Recycled Standard (GRS) is an international, voluntary, full product standard that sets requirements for third-party certification of recycled content, chain of custody, social and environmental practices, and chemical restrictions. Hong Kong company High Fashion (China) Co. Garment Branch is qualified to provide customers with globally recognised GRS products on women’s apparel, dyed fabrics, and packaging.

Image credit: Cotton Roots

Fairtrade cotton is produced in a way that provides economic opportunities for farmers and workers on the ground, while also promoting more sustainable growing practices. UK brand Cotton Roots creates quality polo shirts, T-shirts, aprons, and hoodies using Fairtrade certified cotton.

Image credit: Vaude

The Responsible Wool Standard (RWS) is a voluntary standard that addresses the welfare of sheep and the land they graze on. German brand Vaude is currently working on implementing this standard to their wool across their entire supply chain.

Image credit: Outerknown

Bluesign is an independent authority that provides solutions in sustainable processing and manufacturing to industries and brands. To bear the bluesign® label, manufacturers and brands are required to act responsibly with regard to people, the environment, and resources. Sustainable menswear brand Outerknown relies on Bluesign to get in touch with sustainable chemicals suppliers.

4 Consumer use

Approximately 60% of discarded clothing are disposed of due to weak quality or failures in the garment itself (e.g. pillage, colour fastness properties, tear strength, dimension stability, zipper quality, etc.). [30] The consumer plays a huge role in the environmental impact of a garment — for example, extending the life of clothes by nine extra months can reduce carbon footprints by 20 to 30%. [31]

In this respect, not only should designers and brands be creating garments with lower environmental impact and durable fibres, but also educating wearers on how to care for different fibres so they may keep wearing their clothes for longer.

Image Credit: The Slow Label

Giving consumers information about their clothing enables them to recognise its value. The Slow Label offers an example of how brands can influence how long a garment remains in use as well as offer options for their end-of-life. Their website encourages ways to resell, repair, and give back their clothing, with the information accessible through their circularity.ID® technology, a QR code featured on a button in the clothing. Around 21% of accelerated potential in circularity is directly related to consumer actions in the use phase and end-of-life phase, enabled by conscious consumption and new industry business models [32].

Image credit: Guppyfriend

Each year, around half a million tonnes of plastic microfibres are released into the ocean due to the washing of garments made from synthetic fibres.[33] This is equivalent to more than 50 billion plastic bottles! Microfibre pollution disrupts marine biodiversity and affects our health as it enters our food chains via seafood. Guppyfriend developed a fine mesh laundry bag that traps the microfibres inside during the washing process to prevent them from entering waterways.

Expert Tip

Dr. Christina Dean

CEO and Co-founder of The R Collective

Understanding the fibres in garments and how to care for them is essential for the wearer in order to ensure the piece both lasts and thrives. At The R Collective, we advise our customers to invest only in what they love and to be mindful of the methods and frequency of laundering. We feel it is important for designers and brands to provide information to customers to help them navigate the ever-growing list of fibres we see on our labels. Giving specific information on how to care for different fibres goes above and beyond what most brands provide, with the instructions for delicate or new fibres often defaulting to ‘dry clean only’. It isn’t necessary to wash after one, two, or even three wears — and it’s difficult for consumers to break their habits unless the experts tell them! Beyond this, you can also provide information on alternatives to laundering, such as spot cleaning or simply hanging to air outside to get rid of odours. Repair is also part of care. Let your customers know that you care about their clothes lasting longer. Point your consumers in the right direction and they will be loyal!

5 End-of-life

The acceleration of the fashion supply chain and changing consumer attitudes towards fashion as a disposable commodity has contributed to the exceedingly high levels of textile waste generated worldwide, creating a serious environmental threat. The vast majority of our clothing ends up in landfills or is incinerated, with only 20% of clothing destined for reuse or recycling globally.[34]

Fibre decisions affect all product life cycles, so there is a huge opportunity for design professionals to reduce waste via a circular model for design. Whilst textile recycling has yet to meet the demand for today’s textile waste, championing circular business models is important for offering solutions. Clothing takeback schemes, which reward consumers for giving their unwanted clothing, offer a great example for what responsible circular fashion looks like.

Image credit: Redress

Kate Morris, Redress Design Award 2017 First Prize winner, designed a bright and playful plant-based knitwear collection incorporating recyclability. She chose a mono-material, 100% cotton fibre, and did not add trimmings to her entire collection. This ensured that the textiles could easily re-enter garment production through recycling.

H&M’s takeback programme is an example of recycling in partnership with an outside logistics company. In-house, B2C takeback programmes, such as Eileen Fisher and Worn Wear by Patagonia, upcycle and resell their collected garments. Thred-Up and Vestiaire Collective are C2C platforms that call attention to the value of secondhand clothing.

Expert Tip

Clare Lissaman

Director, Product & Impact of Common Objective

Research and understand the environmental impact of different kinds of fibres through their usage. If you have to use a conventionally produced fabric, you can make it into a garment that can be easily recycled (for example, by ensuring the garment is only one type of fibre). For sourcing more sustainable fibres, band together with other independent fashion labels so you can increase the minimum order of a fabric, which will bring the price down. You can use the Common Objective platform to find other designers or brands who may be interested in doing this.

Footnotes

[1][6][23][26][27][33] Ellen MacArthur Foundation. 2017. A new textiles economy: Redesigning fashion’s future.

[2][13] Textile Exchange. 2022. Preferred Fiber & Materials Market Report 2022.

[3] Cottonworks. 2021. Cotton Trust Protocol Fact Sheet: Comparing Conventional and Organic Cotton Production.

[4] Apparel Science. 2022. Difference Between Conventional Cotton, Organic Cotton, and BCI Cotton.

[5] WRAP. 2017. Valuing Our Clothes: the cost of UK fashion.

[7][11] Board of Intermediate Education, Classification and general properties of textile fibres.

[8] International Archive of Applied Sciences and Technology. 2016. Energy consumption and Carbon footprint of Cotton Yarn Production in textile industry.

[9][15][16] Gullingsrud, Annie. 2017. Fashion Fibers: Designing for Sustainability.

[10] Organic Cotton. Risk of Cotton Processing.

[12] Cotton Australia. 2022. The Cotton Planet.

[14] Textile Exchange. 2021. 2025 Recycled Polyester Challenge.

[17][18] Fletcher, Kate. 2008. Sustainable Fashion & Textiles: Design Journeys.

[19] Sherwood, James. 2019. Closed-loop Recycling of Polymers Using Solvents. Johnson Matthey Technology Review.

[20][21] Close the Loop, End of Life.

[22] WRAP. 2017. WRAP Sustainable Clothing Guide.

[24][32] Global Fashion Agenda. 2020. Fashion on Climate.

[25] Quantis. 2018. Measuring Fashion.

[28] KPMG & Textile Exchange. 2018. Threading the needle: Weaving the Sustainable.

[29] National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology and the Ministry of Commerce. 2022. Implementation Opinions on Accelerating the Recycling of Waste Textiles.

[30] ECOS. 2021. Durable, Repairable and Mainstream: How Ecodesign Can Make Our Textiles Circular.

[31] WRAP. 2013. Design for Longevity Guidance on increasing the active life of clothing.

[34] Global Fashion Agenda. 2017. Pulse of the Fashion Industry.